April 9 - May 31, 2009

Curated by Christof Migone

Diane Landry – Reception and Artist Talk

Tuesday, April 7th, 6 pm

29 McCaul Street, Toronto

An artist talk with Diane Landry, followed by a discussion with Assistant Professor Alison Syme.

A joint presentation with the Koffler Gallery of the Koffler Centre of the Arts.

Michael Snow “Two Radio Solos” - CD Launch

Saturday, April 11th, 1 – 3pm

Art Metropole, 788 King Street West, Toronto

Free Contemporary Art Bus Tour

Sunday April 26th, noon – 5pm

Tour starts at 12noon at Beaver Hall Gallery (29 McCaul Street, Toronto) to Blackwood Gallery, AGYU and Doris McCarthy Gallery.

RSVP (416)736-2100 ext44021

ARTbus

Sunday May 3rd, 11:30am to 5:30pm

Tour departs from Gladstone Hotel (1214 Queen St. W.) to Oakville Galleries, Blackwood Gallery and Art Gallery of Mississauga

Cost: $10. RSVP (905)844-4402

We imagine that the object of our desire is a being that can be

laid down before us, enclosed within a body. Alas! it is the extension

of that being to all the points of space and time that it has occupied

and will occupy.

- Marcel Proust

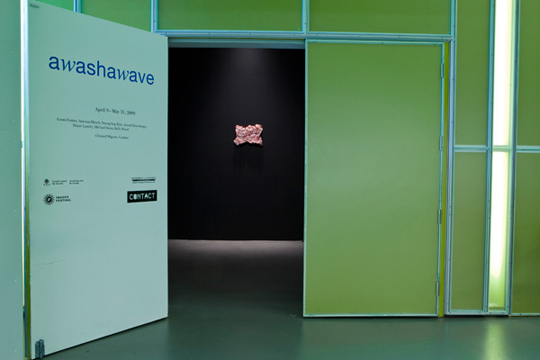

awashawave, with the alliterative title that slips by, is a group exhibition investigating figurative and literal interpretations of inundation and the resulting perceptual tensions and shifts of being one amongst many. In his study on Proust, Beckett stated that “the only fertile research is excavatory, immersive, a contraction of the spirit, a descent. The artist is active, but negatively, shrinking from the nullity of extracircumferential phenomena, drawn in to the core of the eddy.” This exhibition will resist such categorical declaration and opt to pay attention to the inherent fluidity of the eddy. awashawave will epitomize the blur, and wallow in the mud of perception. Examining the shift from the single image to the series, from the fixed to the unmoored, from a discernable point to a dense mass. Examining various facets of the concept of being flooded, awashawave will present a heterogeneous series of works: from a washing machine turned into a praxinoscope (Landry), to an audio work utilizing shortwave radio signals (Snow), to delicate ceramic objects made out of white speaker wire and diffusing sounds of washing (Kim), to images produced by a home-built scanner-camera that fuses digital technology and 19th century photographic techniques (Koroshegyi), to audio tracks converted into dense black and white 'sonic' images (Wood), to a video projection of someone doing the 'wave' in an empty stadium (Hirsch), to a series of abject self-portraits rendered in wax (Fortier).

It's about inundation as opposed to distillation.

The expectation of a thematic exhibition is to present a distilled, filtered view, one that synthesizes research and arranges the selected works in a manner that generates sense. The curatorial essay in particular is expected to coalesce and cohere, to unravel the theme so as to provide a guide which will facilitate the viewer's ability to read and comprehend the thrust of the exhibition in its components and as a whole. Such a prescriptive and predetermined outcome seems ill-suited for an exhibition on inundation. And even the phrasing here should be amended, 'on inundation' impedes the inundation from occurring, it erects a dam (the tautological 'in inundation' would be more apt). To be flooded is to loose one's foothold, one's ground, therefore a more fitting description would be an inundated exhibition. Akin to the immersive properties of an installation but more ambivalent and subtle, awashawave is the mess that washes up on the shore. And as the tide rises it gets swallowed again by the relentless waves. Refuse and refuse. What I am inferring here is that at play is a resistance to the funnel of precision and accuracy in favor of the blur (see the brief curatorial statement which hints at the direction I am delving in here but also counters it by its concision). One of the manners to enact inundation to its fullest extent in a curatorial essay would be to provide the unexpurgated narrative of an exhibition. One that recounts the minutiae of the days immediately prior and following the opening. This entails revealing the mundane details of travel and shipping arrangements as well as the musings of the curator exposed in their inchoate state, prior to the crystallization of cogency. How all of these intertwine constitutes the reality of an exhibition, but rarely is that reality itself exhibited. The merit of that reveal and the success of its translation to text is debatable. The import is not to let predictable failure hamper the exploratory process.

awashawave, with the awkward alliterative title that slips by, but that also arrests with its self-conscious typography and word play, contains a fortuitous abundance of the letter 'a' for Bachelard identifies this letter as the vowel of water.(1) He precedes this by stating that "liquidity is the very desire of language. Language seeks to sink."(2) The lack of specificity of the indefinite article (as opposed to 'the') points to a sunken language. How is this peculiar language, steeped in wallow and swallow, to be considered in relation to modes of communication predicated on dehydration (i.e. an axiomatic system, positivism or the language of predetermined answers)? Deleuze & Guattari depict the indefinite as "the conductor of desire", as an article which is "not indeterminate or undifferentiated, but expresses the pure determination of intensity, intensive difference."(3) Their intent is to keep their disorganized body indistinguishable from desire, keep the fluidity that bathes viscera active and productive. There is a connection to be made here to the tensions between the one and the many (the self amidst the collective) but I would like to defer it for now. Instead, I would like to dwell on the impass my thinking has reached at this early stage of the essay. Keep in mind that the essay form is based on the notion of attempt, of test. While I am veering away from certain formal conventions of the genre, this text remains in that tradition, a proto-essay perhaps. Or a Benjaminian convolute: "The work on the Paris Arcades is taking on a never more mysterious and insistent mien and howls into my nights like a small beast if I have failed to water it at the most distant springs during the day. God knows what it will do when, one of these days, I set it free."(4) Text irrigation.

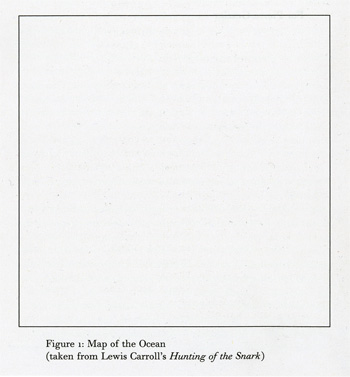

The epigrammatic image in Perec's Species of Spaces is an empty frame identified as a "Map of the Ocean" by Lewis Carroll.(5) The engulfing properties of an ocean transfixes us, Carroll conceptual gesture suggests a void, one faced by anyone given the task to program a space-time. By extension, the gallery space could be viewed as the embodied form of such an oceanic map. A porous container, leaking its perennial reimaginings and recontextualizations. The degree zero of a volume, its empty status temporary, a sign effusing potentiality. It is that potentiality that sometimes affronts and threatens, the public realm is replete with guides and markers and is therefore not equipped to venture without buoys. The gallery is the stationary version of Foucault's boat as he defines it in his "Of Other Spaces" essay: "the boat is a floating piece of space, a place without a place, that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea and that [...] has been simultaneously the greatest reserve of the imagination. The ship is the heterotopia par excellence."(6) My addendum would be that, paradoxically, the only way the boat can float is if it sinks. In other words, it must be porous, must be in conversation with the surrounding. That is what Foucault infers by 'given over', it has a self-awareness of its alien status. A stranger amongst predetermined spaces. I am purposefully conflating boat and ocean here, the two components that constitute the condition of possibility of the voyage of an exhibition. In other words, the thin and frail thread of the known as it makes its way across the expanse of the unknown.

James Joyce responds to the question of Bloom's fascination for water with a remarkable enumeration that focusses on its geophysical attributes, but there is a tinge of metaphysics at work here as well (not to mention the deluge of the list itself).

What in water did Bloom, waterlover, drawer of water, watercarrier, returning to the range, admire?

Its universality: its democratic equality and constancy to its nature in seeking its own level: its vastness in the ocean of Mercator's projection: its unplumbed profundity in the Sundam trench of the Pacific exceeding 8000 fathoms: the restlessness of its waves and surface particles visiting in turn all points of its seaboard: the independence of its units: the variability of states of sea: its hydrostatic quiescence in calm: its hydrokinetic turgidity in neap and spring tides: its subsidence after devastation: its sterility in the circumpolar icecaps, arctic and antarctic: its climatic and commercial significance: its preponderance of 3 to 1 over the dry land of the globe: its indisputable hegemony extending in square leagues over all the region below the subequatorial tropic of Capricorn: the multisecular stability of its primeval basin: its luteofulvous bed: its capacity to dissolve and hold in solution all soluble substances including millions of tons of the most precious metals: its slow erosions of peninsulas and islands, its persistent formation of homothetic islands, peninsulas and downwardtending promontories: its alluvial deposits: its weight and volume and density: its imperturbability in lagoons and highland tarns: its gradation of colours in the torrid and temperate and frigid zones: its vehicular ramifications in continental lakecontained streams and confluent oceanflowing rivers with their tributaries and transoceanic currents, gulfstream, north and south equatorial courses: its violence in seaquakes, waterspouts, Artesian wells, eruptions, torrents, eddies, freshets, spates, groundswells, watersheds, waterpartings, geysers, cataracts, whirlpools, maelstroms, inundations, deluges, cloudbursts: its vast circumterrestrial ahorizontal curve: its secrecy in springs and latent humidity, revealed by rhabdomantic or hygrometric instruments and exemplified by the well by the hole in the wall at Ashtown gate, saturation of air, distillation of dew: the simplicity of its composition, two constituent parts of hydrogen with one constituent part of oxygen: its healing virtues: its buoyancy in the waters of the Dead Sea: its persevering penetrativeness in runnels, gullies, inadequate dams, leaks on shipboard: its properties for cleansing, quenching thirst and fire, nourishing vegetation: its infallibility as paradigm and paragon: its metamorphoses as vapour, mist, cloud, rain, sleet, snow, hail: its strength in rigid hydrants: its variety of forms in loughs and bays and gulfs and bights and guts and lagoons and atolls and archipelagos and sounds and fjords and minches and tidal estuaries and arms of sea: its solidity in glaciers, icebergs, icefloes: its docility in working hydraulic millwheels, turbines, dynamos, electric power stations, bleachworks, tanneries, scutchmills: its utility in canals, rivers, if navigable, floating and graving docks: its potentiality derivable from harnessed tides or watercourses falling from level to level: its submarine fauna and flora (anacoustic, photophobe), numerically, if not literally, the inhabitants of the globe: its ubiquity as constituting 90 percent of the human body: the noxiousness of its effluvia in lacustrine marshes, pestilential fens, faded flowerwater, stagnant pools in the waning moon.(7)

awashawave, an unwieldy but mellifluous word to match the Blackwood Gallery's location: Mississauga. Photo of highway sign provided to mark the imminent arrival of the out-of-town artists, starting tomorrow with Antonia Hirsch from Vancouver and Young-Sup Kim from Seoul.

Imaginary map of awashawave (Blackwood Gallery):

— VIDEO 1 (Michael Snow)

— VIDEO 2 (Antonia Hirsch)

— VIDEO 3 (Kelly Wood)

— VIDEO 4 (Young-Sup Kim)

Imaginary map of awashawave (e-gallery):

— VIDEO 5 (Diane Landry, Louis Fortier)

— VIDEO 6 (Diane Landry, Louis Fortier)

— VIDEO 7 (Michael Snow)

Imaginary map of awashawave (video wall):

— VIDEO 8 (Arnold Koroshegyi)

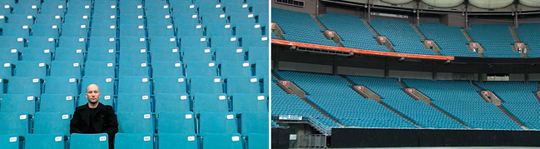

Install views of the billboard-type screens for Antonia Hirsch's video diptych Vox Pop (2008). They are not quite as high in the space as I had imagined them, and their relative position also has shifted from the version I had conjured up (see VIDEO 2 under -9 (March 31, 2009) above). That's to be expected, a floor map and measurements cannot match having the objects in the space.

On one screen, a full circle pan, like a spinning wheel or record on a turntable. On the other screen, a lone scratch causing a skip, a lone body in an invisible crowd, standing up and raising his arms to catch the wave. Does he succeed in sharing the synchrony of the gesture with the invisible crowd or is he confirming the 360 degrees of separation? In Crowds and Power Elias Canetti speculates that "religions [may] begin with these invisible crowds", there is an inherent spectrality in Antonia Hirsch's Vox Pop (2008) that would suggest that the force and scope of totality (hinting at the totalitarian impulse but not wanting to pin it down) is critically addressed here through the solo gesture.(8) Not just solo but solitary, Georges Didi-Huberman offers a proviso for such gestures: "He seemed to be dancing with his solitude, as if it was fundamentally a 'partnered solitude', which is to say, a complex solitude populated by images, dreams and memory. Thus, he danced his solitudes, thereby creating a multiplicity."(9) The staging of the individual's action should also be examined sonically, the muteness of the stadium is deafening. Ralph Ellison poses the question in Invisible Man: "What about those fellows waiting still and silent there on the platform, so still and silent that they clash with the crowd in their very immobility; standing noisy in their very silence; harsh as a cry of terror in their quietness?"(10) The vox populi is loud and clear through an alternate amplification system (also concretely evoked by the billboards), one economical and reductive, evoking foreboding and pathos. In Vox Pop, the constitutive unit of the wave is isolated and itemized, its agency is under question. The sole power of the gesture is in its undermining commentary on power, it's a lowercase power, it's a transient skip on the inexorable progress of the wave on its way to submersion. One minute later the next wave breaks. And so on.

Sunday is the day for to-do lists. TODAY: send personal email invites. TOMORROW: install Kelly Wood piece, connect audio for Michael Snow piece in both galleries, install Young-Sup Kim in Blackwood Gallery, install Louis Fortier pieces in the e|gallery, order vinyl lettering. TUESDAY: Diane Landry talk. WEDNESDAY: Diane installs her washing machines in e|gallery, work on maps for the spaces, Arnold set up his piece on video wall. THURSDAY: The Opening. FRIDAY: closed (Good Friday). SATURDAY: Two Radio Solos CD launch with Michael Snow at Art Metropole.

I forgot to add one thing to the above list: exhausted.

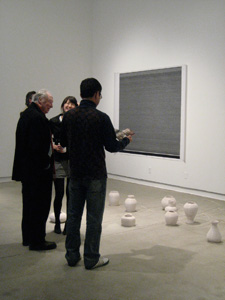

A sample of Young-Sup Kim's objects, made solely out of speaker wire. The speaker wire is functional and will feed the sound to the bare speakers which will be inserted inside each of the twenty objects that will be spread throughout the floor of the Blackwood Gallery.

I have a predilection for the diaristic genre, it's obvious that it is a narrative form that reveals and appeals to the confessional impulse and thereby the voyeuristic and exhibitionist binary. That dynamic can be titillating, but my interest lies more in the torrent of words the format is prone to produce. My attempt to emulate this mode here have not really proved successfull. I am realizing the difficulty in breaking ingrained habits. My writing veers toward the elliptical, it has a propensity for condensed kernels (of dubious merit sometimes). Verbosity seemed to be the way to counter my inclination for elliptical writing. This strategical constraint aimed to loosen the hold of the rational and to free the form of the curatorial essay from its role as road map to the exhibition. awashawave wants you to get lost.

The first entry stated: "It's about inundation as opposed to distillation" and I am prone to distill as opposed to inundate. Counter-currents. I maintain, however, that there is an immersive property to be gleaned from reductive tendencies. I think that it is all in the wavering, the fluctuating. The ambivalence caused by lack does not differ from the one caused by excess. awashawave offers both extremes as ends that meet.

Does stubborn ambivalence and ambiguity have a political dimension? Is the calculated apositioning equatable with standing on the sidelines and acquiescing? The politics of awashawave are left to you.

"A sail! A veil awave upon the waves." (11)

In conjunction with the awashwave exhibition we are very pleased to publish the audio CD re-mastered version of Two Radio Solos by Michael Snow (originally released as a cassette in 1988). Statement by Michael Snow printed on the back cover of the CD:

These 2 short-wave pieces are both "played continuous improvisations. There was no editing, no post-facto electronic alteration. The sounds were found by paying intense attention to fate tuning in and out and between stations, changing bands, bass, treble and volume. The radio played is a circa 1962 Normende (pictured). The gradual change in pitch and speed on SHORT WAVELENGTH is an "accident": batteries were losing power during the recording. The tapes were made at night in a remote North Canadian cabin lit by a kerosene lamp....

Antonia Hirsch's Vox Pop itemized the wave to an absurdist level, emulating Italo Calvino's Mr. Palomar who attempts to read a wave by isolating a single instance of one: "it could perhaps be the key to mastering the world’s complexity by reducing it to its simplest mechanism."(12) Michael Snow also shortens the wave but in the opposite direction and in an altogether different medium. One might say that Snow's Two Radio Solos Snow dwells on the world's complexity. As manifested in the radio signals of shortwave frequencies featured, there is a veritable cornucopian palette of sounds in these lengthy tracks (titled Short Wavelength and The Papaya Plantations): pulses, beats, hisses, tones, cracklings, a Babelian assortment of voices, music of various genres, and noises of all stripes. Their complexity and countless number are foregrounded by Snow's acute listening and fine tuned improvising. He animates these densily populated frequencies from an isolated location —the solitary player in a cabin tuning in the multitude (he echoes the lonely waver in the empty stadium of Vox Pop after all). In The Practice of Everyday Life de Certeau presents a body which is heard but not seen, one that haunts the everyday, a sonic body who emits a spectral presence. And "these are the reminiscences of bodies lodged in ordinary language and marking its path, like white pebbles dropped through the forest of signs."(13) Two Radio Solos inverses that equation, they present a forest of unintelligble sounds with brief moments of recognition, the signs are sporadic amidst the awashed soundscape. But the link is apt nonetheless, and especially given de Certeau's astounding addendum: "An amorous experience, ultimately."(14) de Certeau is portraying the body's persistent presence in language (a thread that Barthes fully mined as well), but one could also readily describe the relationship of the improviser and his instrument as such. The love implied in the act of tuning in, in receiving.

The multi-band chaotic orchestra played (and listened) by Snow in Two Radio Solos are presented as sonic envelopes in both gallery spaces. In one blending in with the sound of Young-Sup Kim's work and in the other with Diane Landry's washing machines. In both instances they are located high on the wall or on the ceiling so that the visitor hears them coming from above, as both ethereal emanations and saturated groundswells.

(There is a link here to the Sirens (in Homer, Kafka, Joyce, Blanchot) that should eventually be made and followed up).

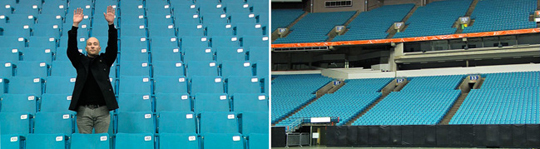

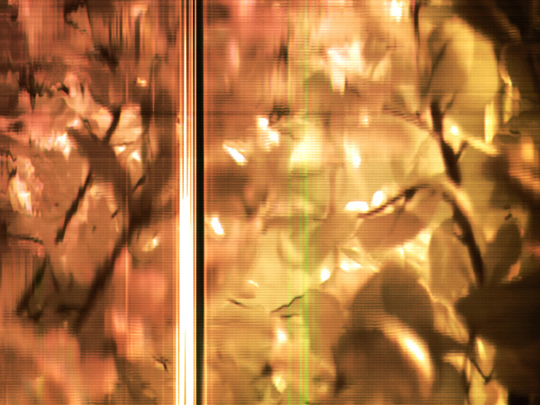

Arnold Koroshegyi's statement about his piece on the video wall of the CCT building:

Rupture (6 minute looped DVD) is a new video piece exploring the association of the photographic blur with the invisible blur of wireless information. Bringing together information aesthetics, locative media and digital photography, Rupture features an unpredictable, aleatory camera that moves across lush, tableau-like photographs of artificial foliage developed from a home-built digital scanner camera (where the focal plane is "exposed" in a series of linear motions, over short intervals of time).

At a distance, the resulting colour-saturated almost hyperreal images appear painting-like, as in a pre-Raphaelite tableau. Zoomed in, however, the streaking artifacts and the pixilated blurs ensuing from a digital camera registering motion (what the computer considers visible defects or loss of information), steer the viewer from any kind of romantic interpretation. Here, the tension between the painterly quality and the digital technological imprint questions the conceptual basis of how we read the out-of-focus in photographic images.

Moreover, the subversive integration of FBI developed surveillance software is what dictates the erratic, arbitrary movements of the video camera through the still photographs: local wireless Internet traffic on a laptop was recorded, then processed and translated it into a visual language which prescribed the trajectory of the video camera movements over the photographs.

Rupture, through the interplay of the moving and static image, unsettles the focus: no longer can the eye contemplate the depth of the painterly photographs or try to discern the shapes beneath the pixilated blurs. Instead, the invisible blur of information is made visible through volatile camera movements that force the viewer's eye to shift strangely across the screen: perception flounders, inundated by technology and artifice.

In reference to the imaginary map of awashawave in the form of a set of impromptu video clips posted above under -7 (March 31, 2009)and -8 (April 1, 2009) here now are the same spaces with the works installed, the actualized map of the exhibition, accompanied by quick and simple descriptions of each work:

Actualized map of awashawave (Blackwood Gallery):

— VIDEO 1 (entrance, title wall, Michael Snow track 1)

— VIDEO 2 (Young-Sup Kim)

— VIDEO 3 (Antonia Hirsch)

— VIDEO 4 (Kelly Wood 1)

— VIDEO 5 (Kelly Wood 2)

Actualized map of awashawave (e-gallery):

— VIDEO 6 (Diane Landry, Louis Fortier, Michael Snow track 2)

— VIDEO 7 (Diane Landry, Louis Fortier, Michael Snow track 2)

Actualized map of awashawave (video wall):

— VIDEO 8 (Arnold Koroshegyi)

Views of Diane Landry's Madonnas as they were being installed in the e|gallery. Professor Alison Syme was commissioned to write an essay specifically focussing on this piece; "What Comes Out in the Wash" can be found below on this page. It provides a historical background to the technical development of the praxinoscope, the 19th century optical device that Landry is utilizing in Madonnas. Syme also deftly articulates the correlations between the praxinoscope and the washing machine in the context of the transformations of labor and commodity in the late 19th century —a foundational period for modernity, consequently, the issues raised by these transformations ineluctably remain present-day concerns.

Kelly Wood's two colourgenic prints culled from her Binary Sound Series (2008) were produced by the deceptively (and refreshingly) simple procedure of opening up a sound file in Photoshop. The size of the file (i.e. the length of the track) automatically determined the size of the image, no resizing was done by the artist. Duration translated to area. Time to space. Sound art, on the wall, as an image, at last. A description of the sound sources for the two selected works:

The Nihilist Spasm Band – An Appeal To Reason (1984)

Formed in 1965, and based out of London, Ontario, the Nihilist Spasm Band continue to produce a unique form of free improvised noise using a variety of specially made electric and acoustic instruments. Members include artists Greg Curnoe (1936-1992), John Boyle (1941-), and Murray Favro (1940-). An Appeal To Reason was recorded live at the Forest City Gallery in London, Ontario, an artist-run centre that has hosted many of the band’s performances which have happened nearly every Monday night for more than three decades.

John Oswald – Bell Speeds (1983-90)

John Oswald, born in Kitchener, Ontario in 1953, is a composer, musician, dance choreographer and visual artist best known for his “plunderphonic” recordings which he assembles using freely appropriated samples of popular music. After the release of the full-length album Plunderphonic (1989), Oswald faced legal action for alleged copyright infringement by lawyers representing Michael Jackson, and was forced to destroy existing copies of the CD. Bell Speeds is composed of the sound of a bell electronically processed to produce a range of tones in multiple layers.

Louis Fortier made some variations of his Le Sénat series especially for this exhibition. Compared to the ones pictured below (in the Artist Images & Bios section) you will notice that the ones pictured here, just as they were being removed from their shipping crate, are more compressed, condensed, collapsed. They accentuate even further the deformation and the merging of the variations —no longer a series of faces but a single face in motion. Writing on 'pulsation' in Formless: A User’s Guide, Yve-Alain Bois wrote that it "involves an endless beat that punctures the disembodied self-closure of pure visuality and incites an irruption of the carnal." (15) The carnal is preeminent in these portraits, they forego depiction in favor of a distortion close afield from the disgust associated with abject flesh. Kristeva quoted in an entry by Rosalind Krauss in the aforementioned guide: "The abject-as-intermediary [ie. between subject and object, but neither of the two] is thus a matter of both uncrossable boundaries and undifferentiable substances, which is to say a subject position that seems to cancel the very subject it is operating to locate, and an object relation from which the definability of the object (and thus its objecthood) disappears."(16) These wax 'pulsed' portraits embody precisely this, Fortier's face disappears in its repetition, representation is swallowed up by an undeniable mass.

(soon)

(at some point)

(in time)

(in progress)

This hybrid text is close to its end, but (unlike print publication) the advantage of online publishing is that this doesn't necessarily entail closure. No seal, no binding, no finishing. The text is always open (hence The Opening). Many more threads need to be explored (I have left some hints along the way). Several of the works have not yet been properly discussed. They all merit attention and consideration. There is a certain freedom in leaving this unfinished, it is difficult to reconcile however with one's own expectations for a definite statement, an encapsulating summary. A significant strain of thought treads on a similar path of skirting around resolution (surfacing particularly from the 19th century onwards). Blanchot defined writing as the act of "trac[ing] a circle within which the outside of any circle would inscribe itself."(17) To be inside the outside, to be outside the inside. A container that leaks.

Some writers nod in this directionless direction but cannot resist the comfort of a teleological assertion. Authority and power invariably come into play as one negotiates the stakes involved, to undermine them in a meaningful and structural manner is a difficult task. There is a distinct possibility that my position as director/curator does not permit me to even invoke such a strategy. Nevertheless, here we are both, in a provisional here and now. Let's leave it at that.

Loose beginnings, loose ends.

awashawave is both the first show (a naive melody) and the last (a considered culmination).

It is both the only show (complete focus and attention) and only a show (part of a continuity).

"It is not down in any map; true places never are." (18)

Diane Landry’s Madonnas (2007) revive a 19th-century optical device: the praxinoscope. From the Greek praxis (action), a praxinoscope is an instrument for viewing action or motion. Invented in 1876 and patented in 1877 by a French science teacher, Charles-Émile Reynaud, the praxinoscope was one of many 19th-century optical devices that exploited retinal after-images to create an illusion. The thaumatrope or ‘wonder-turner,’ which became a popular household toy in the 1820s, was the simplest and earliest of these devices. It consisted of a circular or square piece of card with different images painted on each side. Strings attached to the edges allowed the viewer to twirl the card; when spun, the images optically combined. Visual perception is not instantaneous: if it were we’d be able to isolate every spoke in a spinning bicycle wheel. Optical impressions linger, so the spokes of a moving wheel blur together. The thaumatrope made this physiological phenomenon plain, as erstwhile isolated birds and cages, hats and heads, horses and riders, dancing partners, and the like came together in the observing eye. Dr. John Paris, a British physician, used this simple apparatus to demonstrate the persistence of vision to his medical peers at the Royal College of Physicians in 1824.

Optical devices developed in the decades after the thaumatrope often used image sequences – of figures dancing, animals jumping, etc. – to create the illusion of continuous motion. The phenakistoscope or ‘trick-viewer,’ invented by the Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau in 1833, consisted of a perforated, spinnable disc attached to a handle. Drawn or printed images depicting the successive positions of figures and objects in motion decorated the outer half of the disc while vertical slits fanned out from the centre to the middle of the circle. The viewer held the device in front of the mirror, looked through one of the slits at the reflected image in the mirror, then spun the disc. The regular interruption of the image flow created by the slit structure prevented the images from blurring into one another and allowed for the proto-cinematic illusion of continuous action. The zoetrope or ‘life-turner’ also made use of slits to punctuate the flow of images, but it was no longer a hand-held device. Shaped rather like a table lamp, the zoetrope was a cylindrical drum with a solid bottom and no top that rested and spun above a wooden base and column. Twelve or more successive images printed on an insertable band decorated the bottom half of the interior wall of the drum while an equal number of regularly spaced slits perforated the drum above, in between the images. When spun, a number of viewers stationed at different points around the circumference could experience the illusion.

Reynaud added two features to the basic design of the zoetrope to create the praxinoscope. He placed a cylinder made up of vertical, rectangular pieces of mirror at the centre of the drum, and a lamp above it to illuminate the interior of the device. The viewer no longer peered through slits to see the illusion, but looked from above at the mirrored cylinder, which reflected the images lining the drum – like those for the zoetrope, printed on insertable bands. When the drum was spun, figures danced and moved in the mirror. The overall effect was brighter and more colourful than that created by the zoetrope or phenakistoscope, and Reynaud’s invention was a popular success: over 100,000 were sold in the first year.(1) His subsequent alterations to the device (discussed below) transformed it into an image projector, a forerunner of Thomas Edison’s kinetoscopes, developed in the 1890s, and the first silent films.

Landry’s Madonnas are modified praxinoscopes. Instead of drums with central cylinders of mirrors, Landry’s versions consist of flat, horizontal discs of 12 images that are reflected in 12 mirrors, angled up and out from the centre of the discs, that form upside-down conical frustums. The discs and mirror frustums sit above lidless, white, top-loading washing machines on columnar extensions of the agitators. White fluorescent lights inside the tubs illuminate the translucent discs and mirror images from below. The photographic images on each disc consist of the head and shoulders of a middle-aged white woman in different positions; when one of the washing machines is started the woman appears to nod or bow up and down in the mirrored frustum. The familiar, rhythmic chug of the washing machine as the agitator spins the basket back and forth in the wash cycle accompanies her repeated movement.

The washing machine and praxinoscope form a curious but compatible couple. Jonathan Crary has argued that 19th-century optical devices helped shape the modern subject. Developed by scientists to help demonstrate or study the physiology of vision, or to help visualize phenomena the unaided human eye found difficult to discern, these instruments quickly became staples of middle-class entertainment and patterns of consumption. Tools of science and engaging toys, they assisted the bourgeois subject’s pursuit of both knowledge and pleasure. At the same time, though, they subjected the viewer’s body to a kind of mechanistic control. As Crary puts it, in using these optical instruments the viewer’s body was “aligned with and operating an assemblage of turning and regularly moving wheeled parts.”(2) Science, entertainment, and the proliferation of commodities were inseparable from the rationalization of time and bodies in modern culture. Marshalling attention and disciplining the body (which, through repeated use became comfortable with proximity to and physical integration with machinery), optical devices like the praxinoscope produced a new kind of modern observer – one literally geared toward a new type of visual consumption, of mobile and endlessly exchangeable images.

Like 19th-century optical instruments, the washing machine was both a technological triumph and an essential commodity for the middle-class household. Rotary washers were invented in the 1850s, but the first successful manufacturing and marketing of domestic washing machines occurred in the 1870s, the same decade as the praxinoscope.(3) Beyond this historical coincidence, washing machines and optical devices were also linked by a material connection, though admittedly a fragile, tenuous, and ephemeral one. Many of the optical devices invented in the 19th century were designed by scientists who studied the washing machine’s most essential component: soapy water. To be precise, they studied the physics of soap bubbles and films. John Paris, popularizer of the thaumatrope, discussed the physics and optics of soap bubbles in his Philosophy in Sport Made Science in Earnest;(4) Joseph Plateau, inventor of the phenakistoscope, used bubbles to theorize capillarity, surface tension, and minimal surface problems; and the first series of praxinoscope bands issued by Reynaud included a strip of soap bubbles. The historian of science Simon Schaffer has even argued that it was the desire to capture “the playful kinematics of drops and films” that led to the design of apparatuses capable of reproducing transient phenomena, that is, to the development of the optical devices discussed here.(5) Paradoxically, these machines capable of mastering transience assisted in the commodification of images and the creation of a constantly shifting visual field flooded with ephemera. Similarly, the washing machine that harnessed the cleansing power of soap bubbles and promised freedom from labour and industry was itself part of a system of fetishized commodities that mechanized and isolated producers and consumers.

Both the historical praxinoscope and Landry’s 21st-century versions exhibit an ambivalent relation to commodity phantasmagoria. As Crary points out, in the praxinoscope and earlier optical devices, the workings behind the production of the illusion were laid bare; viewers simultaneously enjoyed the fiction and the demonstration of its production. The praxinoscope was one of the last exemplars of such mechanism-exposing illusion devices: in 1879 Reynaud unveiled the ‘Théatre-Praxinoscope,’ a praxinoscope with a proscenium stage that hid the turning drum and mirrors; the phantasm, framed by curtains, was now only available from one point of view. Reynaud then developed a projecting praxinoscope in 1888, called the ‘Théatre Optique,’ which directed viewers’ attention away from the device itself, introducing an ever-widening gap between the means of production and the space of illusion. These increasingly phantasmagoric spectacles obscured “the form of subjection”(6) the devices themselves entailed. Placed on white pedestals and bathed in auratic light, Landry’s moving madonnas are illusionist spectacles, but they also foreground their mechanisms and, as the figures are literally incorporated into the machinery of domesticity, one form of subjection commodity culture entails. The artist has described her piece as an “homage and hymn to the work of women all over the world,”(7) to their patient performance of endless, repetitive, mechanical, domestic tasks. In reworking the praxinoscope and partially laying bare the apparatus by which her moving pictures are made (the electricity cords are hidden beneath carpets), Landry also exposes the way mothers – household madonnas – are products of industrial capitalism’s most basic tenets: private property and the division of labour.

What is it about commodities, though, that gives rise to mystification? A commodity, Marx tells us, “appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood. Its analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.” He illustrates his point with an example: a table. The wood it is made of is not mysterious, nor is the table’s function. The table itself, though, “so soon as it steps forth as a commodity […] is changed into something transcendent.” More animate and imaginate than the workers who made it, the table “not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than ‘table-turning’ ever was.”(8) Table-turning ostensibly occurs when spirits invoked at a séance spin – literally animate – the tabletop. In Marx’s image, commodities give rise to phantasms that, grotesquely, supersede human interactions: with commodity culture imaginary relations between things become more important than actual relations between persons.

Landry’s spinning discs, like Marx’s hypothetical tabletop, create the illusion of animation and draw on Western religious mysteries. Her madonnas are spotless appliances, exactly what virgin mothers should be: obliging, pure vessels with wondrous stain-removing powers. Theological niceties indeed! Commodity and religious fetishes in one, these domestic goddesses, angels of the house, perform ritual motions, offering viewers absolution just as their hollow bodies promise cleansing through watery ablution. Crary discusses the modern observer as a subject in compliance as well as a viewer: aligned and allied with machinery, the observer, however unwittingly, observes (obeys) the rules of capitalist production. Landry brings the notion of religious observation into this constellation of meanings, as well as the supplicatory – not to say appealing – aspect of appliances.

As modified readymades, the Madonnas are kin to Duchamp’s urinal with its Marian silhouette; they belong to the world of plumbing, after all. They also reach back, though, to earlier arts. If Landry’s piece overtly employs the technology of the praxinoscope, it implicitly evokes an earlier animating and entertaining device: the marionette. The term “marionette” refers to puppets operated by strings or wires and persons who can be controlled or manipulated; etymologically it derives from images of the Virgin Mary and thus links to centuries-old forms of superstition and ritual. Landry’s washing machines are rotary votaries; the madonnas’ jerky head movements are puppet-like, as is their “acquiescence” (the artist’s term) to their “mind-numbing and poorly paid work.”

If they are made puppet- or automaton-like, though, these woman-machines are something more monstrous too. Traditional praxinoscope image sequences separate the successive images by lines or blank space. In Landry’s piece, however, the still images are fused at the shoulders. When one of the washing machines is activated, the viewer sees three heads on a single torso nodding up and down in quick succession; the sheltering Madonna becomes a mutant trinity, twisting in agitation, churning at the observer’s approach. Or rather, the constantly scanning figure becomes a forbidding Cerberus, the three-headed dog who guards the river Styx separating the world of the living from that of the dead. Although waterless, the washing machine may still be a kind of whirlpool – a conduit to the underworld. It’s certainly a tide trap. Commodities, like table-turning, it would seem, can conjure up more than one bargained for.

The lights in the machines cannot banish the shadows. Landry’s modified praxinoscopes, then, show us that not everything comes out in the wash. Her madonnas are a decidedly maculate conception: spectres of marks haunt this laundry, which calls attention to the human cost of amenities.

Alison Syme is an Assistant Professor of Modern Art in the Centre for Visual and Media Culture at the University of Toronto at Mississauga. Her first book, A Touch of Blossom: John Singer Sargent and the Queer Flora of Fin-de-Siècle Art, is forthcoming from Penn State University Press. While she specializes in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art, she has also published on contemporary work in Art Journal.

awashawave, with the alliterative title that slips by, is a group exhibition investigating figurative and literal interpretations of inundation and the resulting perceptual tensions and shifts of being one amongst many. In his study on Proust, Beckett stated that “the only fertile research is excavatory, immersive, a contraction of the spirit, a descent. The artist is active, but negatively, shrinking from the nullity of extracircumferential phenomena, drawn in to the core of the eddy.” This exhibition will resist such categorical declaration and opt to pay attention to the inherent fluidity of the eddy. awashawave will epitomize the blur, and wallow in the mud of perception. Examining the shift from the single image to the series, from the fixed to the unmoored, from a discernable point to a dense mass. Examining various facets of the concept of being flooded, awashawave will present a heterogeneous series of works: from a washing machine turned into a praxinoscope (Landry), to an audio work utilizing shortwave radio signals (Snow), to delicate ceramic objects made out of white speaker wire and diffusing sounds of washing (Kim), to images produced by a home-built scanner-camera that fuses digital technology and 19th century photographic techniques (Koroshegyi), to audio tracks converted into dense black and white 'sonic' images (Wood), to a video projection of someone doing the 'wave' in an empty stadium (Hirsch), to a series of abject self-portraits rendered in wax (Fortier).

Louis Fortier (Montreal) "Le Sénat" (2008)

Louis Fortier lives in Montréal. He received his BFA from Université Laval in Québec and he completed his MFA in 1994 at Université du Québec à Montréal. He has participated in a number of solo and group exhibitions throughout Québec, namely at Galerie B-312, Plein Sud, Clark, Axenéo7, la chambre blanche and l’Œil de Poisson. In 2007 he was in the exhibition La tête au ventre curated by Mathieu Beauséjour presented at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery, as well as Hot Wax at The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, St.John’s, NL (curated by Andria Hickey). In 2008/2009 he was featured in It happened in your neighbourhoud: Contemporary Art in Québec, curated by Nathalie de Blois at the Musée du Québec.

http://www.galeriedonaldbrowne.com/

Galerie Donald Browne

Antonia Hirsch (Vancouver) “Vox Pop” (2008)

Antonia Hirsch is a Vancouver-based artist who has received critical attention for both national and international exhibitions, having presented her work at such institutions as Program (Berlin), the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and the Contemporary Art Gallery (Vancouver). Her work has been featured in solo exhibitions at Gallery 101, Ottawa (2007), the Charles H. Scott Gallery (2006) and Artspeak Gallery (2003) in Vancouver, the Kitchener Waterloo Art Gallery (2003) and Gallery 44 in Toronto (2001). In 2004, she was awarded the Canada Council Studio at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris. Her work can be found in public collections such as the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Canada Council Art Bank and the Sackner Archive of Concrete & Visual Poetry, Miami Beach. Her most recent video project, Vox Pop, premiered in 2008 on large-scale, dual outdoor video billboards in downtown Vancouver. A public art project, commissioned for the new campus of the Vancouver Community College is being inaugurated in March 2009. Additional information on the artist is available at antoniahirsch.com.

http://www.antoniahirsch.com/projects/vox-pop/1

Young-Sup Kim (Seoul) "Co-existence_Cable Porcelain & Sound" (2006)

Young-Sup Kim, born 1972 in Dang-Jin/South Korea, lives and works in Saarbrücken. Sound installation and composition. 1990–2000 studied visual arts at the Sea-Jong University in Seoul, diploma. Since 2002 studies audiovisual art at the HBK Saar under Prof. Christina Kubisch. 2003 solo exhibition Gehaltene Klänge at the tage für neue musik, Akademie für Tonkunst Darmstadt and 2004 "BLAUE GROTTE" at Münchhof Hochspeyer.

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/include/print.asp?newsIdx=10992

http://www.sonambiente.net/en/05_laboratorium/5M3_kim.html

Arnold Koroshegyi (Toronto) "Rupture" (2008)

Working in photography, print media and installation, Arnold Koroshegyi has exhibited across Canada and the U.S. His photographic work explores many different traditions of the medium— ranging from a descriptive style series on Unfinished Projects to an investigation of the out-of-focus aesthetic using a home-built scanner-camera that melds digital imaging and 19th century photographic techniques. Currently, Koroshegyi is developing a camera that incorporates locative media, surveillance software and remote sensing technology to create large-scale photographs of electro-climate landscapes. Koroshegyi completed a Masters of Fine Arts at the University of Western Ontario in 2006.

Diane Landry (Quebec) “Madonnas” (2007)

As a multidisciplinary artist, Diane Landry designs original performances, installations with automation, audio sculptures and works she qualifies as “mouvelles”. She has exhibited and performed extensively in Canada, U.S., Europe and Australia. She also realized major public commission for Quebec province. In 2005, she received a Murphy and Cadogan Fellowship Award from the San Francisco Foundation and in 2006, she completed an MFA at Stanford University. In Québec she is the recipient of several prestigious prizes. She has worked also as resident artist at Oboro (Montréal), Avatar (Québec), The Banff Centre (Alberta), Buenos Aires (Argentina), Marseille (France), Utica (NY). In 2008, Landry was the recipient of the six months residency at Le studio du Québec in New York.

http://dianelandry.com/

http://dianelandry.com/dianelandry_2007/Diane_Landry_menu07/p_mouvelles/eaux_volees_eng.html

Michael Snow (Toronto) "Two Radio Solos" (1988)

Internationally acclaimed as an experimental filmmaker, Michael Snow is one of Canada’s most important living artists, distinguished as a highly accomplished musician, visual artist, composer, writer, and sculptor. Dazzling in his ability to switch from one medium to another outside of any predictable sequence, and noted for a multi-disciplinary approach to his work, Snow continually challenges notions of content and form, seeing and representation.

Kelly Wood (London) “Binary Sound Series” (2008)

Kelly Wood was born in Toronto, in 1962. She received her MFA from the University of British Columbia in 1996. She is currently on faculty in the Visual Arts Department at the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at various museums and galleries. Wood's work has been previously shown in Canada at The Power Plant Gallery, The Art Gallery of Ontario and the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography. She is represented by Catriona Jeffries Gallery of Vancouver.

http://www.catrionajeffries.com/b_k_wood_works.html

Generously supported by the Arts Council of Korea, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Trillium Foundation, Images Festival and Contact Festival.